My dog’s tail is a study in perpetual motion. It wags when he’s happy and when he’s nervous, when he leaves a room and when he enters one, when he stands in a doorway snorting at me in an attempt to communicate his desperate desire for a walk or a toy or a treat. Even late at night, when I’m reading in bed and he’s asleep on the floor beside me, I’ll hear the thwap! thwap! thwap! of his tail, twitching while he slumbers.

Dogs may not have voices, but they have very active tails, and they rely heavily on these furry appendages to communicate. A fast, wagging tail can signal excitement and playfulness, whereas a tail tucked between the legs is a sign of submission. A dog that’s feeling aroused, confident, or aggressive may hold his tail up high, while a relaxed pooch lets his tail hang down lower and looser. These tail movements provide important clues about how a dog is feeling–especially to other canines that may be sharing the same sidewalk or dog park.

That’s another reason, experts have argued, to object to tail docking, a barbaric procedure in which several inches of a puppy’s tail are amputated, often without anesthesia. The pain and suffering that cosmetic tail docking can cause are reason enough to oppose the practice, and they are, indeed, the most commonly mentioned objections. Less often discussed, however, is the possibility that removing most of a dog’s tail may actually hamper its ability to communicate with the rest of its species.

I recently came across an ingenious little study that illuminates this problem. The study–run by two biologists at Canada’s University of Victoria and published in the journal Behavior in 2008–makes use of my new favorite experimental apparatus: a life-sized robotic dog.

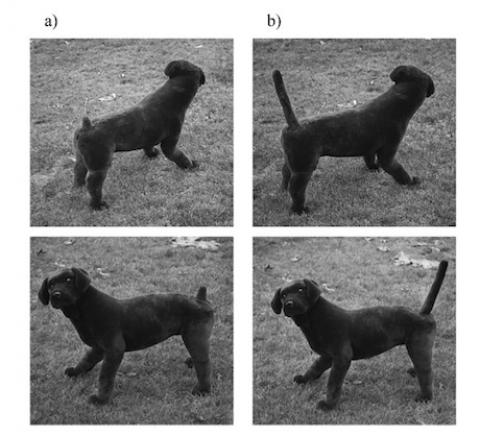

The faux dog–made of synthetic fur, wire, and cotton–resembled a black Lab and had two different detachable tails: one short (9 cm in length) and one long (30 cm). A motor mounted inside the dog’s wire frame allowed the researchers to make both of these tails move using a remote control.

The scientists set the robotic dog out in “areas of high off-leash domestic dog activity” in Canada, and videotaped nearly 500 different real dogs approaching the impostor under four different conditions: when the robot’s tail was long and still, long and moving, short and still, and short and moving.

The results varied according to the size of the dogs the researchers were observing. Dogs smaller than the robot were cautious in approaching the impostor, regardless of the tail length and movement. Of course, such caution makes sense when dealing with a strange beast that could be twice your size.

It was among the large dogs that the interesting behaviors emerged. These dogs were most likely to approach the robotic model when the robot had a long, moving tail. (They did so 91.4% of the time.) That makes sense, the researchers say. “Because the long tail was flexible, the simulated motion appeared to us to resemble that of a loose, wagging tail of a real dog,” they write. This kind of loose wag is often an invitation to play–and a social signal that the wagging dog means no harm.

On the other hand, a dog that is holding its tail perfectly still isn’t giving off such obvious “come hither” signals, and large dogs approached the robot with a long, still tail significantly less frequently–only 74.4% of the time.

But when the researchers swapped the long tail for the short one, these preferences disappeared. Large dogs approached a short-tailed robot with a wagging tail just as often as one with a motionless tail (85.2% and 82.2% of the time, respectively). These findings suggest that the dogs were less able to discriminate between a tail that’s wagging playfully and one that’s standing still and erect when the tail itself is short. “It appears that the signals communicated by differences in tail motion were most effectively conveyed when the tail was long,” the scientists write.

The large dogs were also twice as likely to pause while approaching the short-tailed models, perhaps using that time to try to decipher whether they should continue moving closer. As the researchers put it in their paper, “As the efficacy of a visual signal is related to its visibility … it may be that larger dogs had a harder time interpreting the ‘intentions’ of the model when the tail was short.”

Taken together, the findings suggest that docking a dog’s tail may impair its ability to communicate effectively with its canine comrades. And it’s yet another reason–if there weren’t enough already–to put a stop to the cosmetic amputation of dog tails.

Reference: Leaver & Reimchen. (2008). Behavioural responses of Canis familiaris to different tail lengths of a remotely-controlled life-size dog replica Behaviour, 145 (3), 377-390 DOI: 10.1163/156853908783402894

Spread the word