The 3-to-1 victory of the United Automobile Workers in a National Labor Relations Board election at Volkswagen’s Chattanooga factory last Friday has been the big news on the labor front. For the first time in decades, a Deep South auto plant has been organized, with over 4,200 production workers soon to be covered by a collective-bargaining agreement.

But success in Chattanooga, on the third try in the last decade, might not have been possible without the growing influence of a Brooklyn/Detroit-based organization called Labor Notes. As the news flashed north that the UAW had finally won, more than 4,700 labor activists were assembled at Labor Notes’ conference in an airport hotel near Chicago. The news was electrifying, but they were not there merely to celebrate.

Labor Notes is both a monthly magazine and an organization that publishes books and pamphlets and holds conferences and workshops seeking to “put the movement back in the labor movement.” It was founded in 1979 by Trotskyist-oriented New Left radicals whose post-’60s “turn toward the working class” took many out of the classroom and into the factories, mills, and trucking barns of Middle America.

The group began holding biennial conferences in the early 1980s. During an era of union defeat and concession bargaining, these meetings gave shelter, comradeship, and a measure of inspiration to the scattered radicals and oppositionists who could still be found in many trade unions. Labor Notes fought the idea that a new era of labor-management cooperation was the path toward industrial renewal and union survival, but its staffers and partisans were never simply ideologues. Labor Notes published columns and put out handbooks on grievance handling, worker engagement, strike mobilization, running for office, and all the nuts-and-bolts problems facing unionists and organizers in difficult times. One of the most successful was A Troublemaker’s Handbook, first published in 1991 and continuously updated ever since. It was packed with tactics, strategies, and examples of how unions were built and how they remain strong. At its conferences, Labor Notes celebrated movement troublemakers and successful militants, but perhaps even more important, it hosted panels where speakers offered practical, on-the-ground solutions informed by a movement-building union ideology.

Among the 300-plus panels and workshops at the 2024 Labor Notes meeting were those entitled “Decoding Your Contract,” “Assertive Grievance Handling,” “Secrets of a Successful Organizer: Beating Apathy,” “Running for Union Office: How We Did It,” “How to Spot an Unfair Labor Practice and What to Do With It,” and “Lessons From the UPS Contract Campaign.” Such issues are hardly alien to the larger union movement, and most labor organizations have their own educational departments that run workshops and trainings. But the cross-pollination and networking built into the Labor Notes experience gives to these otherwise prosaic talk sessions an animating excitement that is also entirely practical. In the run-up to last week’s conference, Hannah Allison-Natale, an organizer of low-wage public employees in Kansas, appealed for funds: “Two years ago, I went to the Labor Notes conference alone and realized what a difference it could make in our organizing if my coworkers could come too. This year we are trying to bring eight workers to Labor Notes … Can you chip in to help us reach our goal of $6,000?”

That was a sentiment not of Allison-Natale alone. The conference, says Dan DiMaggio, a Labor Notes editor, offers unionists the chance to “see the possibility of what a real labor movement can do,” while at the same time providing a safe, neutral space where no votes or debate would be held on either the election of union officers or the passage of resolutions. There were scores of panels and workshops where unionists with similar interests or occupations—from food service to the building trades and from high tech to dead-tree media—could exchange ideas and connect. It’s a place “for training and inspiration,” says DiMaggio.

An increasingly large cohort of trade union leaders agree. Members of organizations with a left-wing pedigree or internal reform movements, including the United Electrical Workers, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, plus a series of reform movements in the UAW, and the Teamsters for a Democratic Union, have long had a presence at Labor Notes. This year, the UAW’s Unite All Workers for Democracy, the caucus largely responsible for electing a reform slate to that union’s leadership, was highly visible at the conference. (With historian Toni Gilpin, I was on a panel with UAWD activists reviewing and re-evaluating the leadership and legacy of longtime UAW president Walter Reuther.)

But union dissidents are no longer the main source of Labor Notes attendance. Beginning in the years after the Great Recession, a number of important unions began to subsidize increasingly large delegations, often as a consequence of having a more militant leadership or facing a looming contract fight. Thus, the NewsGuild, a division of the Communications Workers of America, sent more than 100 members to last week’s conference; the Association of Professional Flight Attendants, gearing up for a contract fight and possible strike at American Airlines, subsidized 90 members, while other airline unions sent another 60. There were at least 200 UAW members there, with many from the newly expanded ranks of academic workers, largely from the East and West Coasts. There were dozens of teachers from Massachusetts, where affiliates of the National Education Association conducted a series of illegal strikes, and 25 undergrads from the University of Oregon organizing a union there. A cross-craft, cross-union caucus of railway workers, energized by the 2023 UAW strike and President Biden’s suspension of a 2022 rail strike, had a large presence at the conference. The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, a union not known for much of a left-wing past, sent at least 65 members, and the 30,000-member International Association of Machinists District 751, facing its first Boeing contract fight in a decade, sent their president and a few others. There were 100 Amazon workers and at least 30 from Starbucks.

All this explains why Labor Notes conferences, once assembling about a thousand every two years, are now bursting at the seams. DiMaggio reports that after the conference registration opened, 2,000 ended up on the wait list within a few days. Had Labor Notes engaged an even bigger venue, he estimates that eight to ten thousand people might have attended.

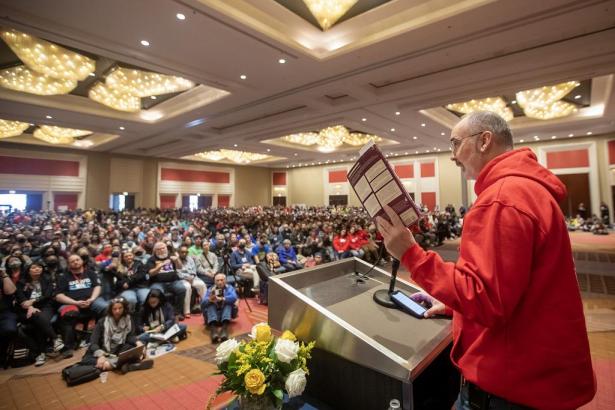

UAW President Shawn Fain was the conference rock star, but also a validator of the Labor Notes ethos. After celebrating in Chattanooga the union victory over VW, Fain flew to Chicago where he joined other UAW officers and staffers at the Labor Notes fundraising dinner and later took part in a Sunday morning workshop, “Back in the Fight: A New Day for Labor.” In his keynote remarks offered at the conference conclusion, where more than 4,000 remained to cheer his class struggle rhetoric, Fain told the crowd of his reliance on the Bible, but then said, “As a young union activist I had another bible, it is this book right here, called A Troublemaker’s Handbook, from Labor Notes. This was my bible and it taught me how to fight the boss. This bible taught me another kind of faith. It taught me faith in the membership, it taught me faith in the working class. And it is that faith that carried the UAW to our new chapter in history.”

Quite an endorsement, but Labor Notes has hardly discovered the ultimate key to union power and renewal. Notably absent from the Labor Notes workshops and plenaries was any discussion of electoral politics. Indeed, the only politician to address the conference was Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson, whose short talk largely emphasized his roots in the Chicago Teachers Union, whose reform leadership has made frequent appearances at Labor Notes conferences. Nothing was said about the elections this November or the prospects for a more potent labor engagement in electoral politics and governance, a topic absent from virtually every workshop and talk I attended—with the notable exception of one convened by labor lawyers, who were terrified of a Trump-dominated National Labor Relations Board.

One reason for that silence is that President Biden, despite his claim to being the most pro-union president in history, inspires little enthusiasm. But the silence is also a product of Labor Notes history: Its founders and many in each successive generation of editors have long favored formation of a labor party. That gambit seems out of reach today, but it can still evoke divisive debate and sectarian rupture. Equally important, the propensity of so many unions to turn themselves every two years into door-knocking adjuncts of the Democratic Party has struck many Labor Notes cadres as subversive of the more vital task: organizing and mobilizing workers against the boss.

The 2023 labor upsurge celebrated at the Labor Notes convention, however, was not merely the product of agitation and organization from below. Since the era of the Great Depression when the Congress of Industrial Organizations burst onto the national scene, the labor movement has been a fundamentally political project whose success depends on a compelling set of ideas and institutions, both self-made and governmental, to give labor’s cause power and legitimacy. The union movement’s comeback in recent years could not have taken place without the existence of a set of political initiatives that generated both low unemployment and a high level of government-guided business investment. And that is just a start in creating the economic and ideological environment that can shift power from capital to labor. Industrial militancy is therefore indispensable, but hardly sufficient to the new world envisioned by those who will attend Labor Notes conferences in the future.

Nelson Lichtenstein teaches history at the University of California, Santa Barbara. His latest book is ‘A Fabulous Failure: The Clinton Presidency and the Transformation of American Capitalism.’

The American Prospect is devoted to promoting informed discussion on public policy from a progressive perspective. In print and online, the Prospect brings a narrative, journalistic approach to complex issues, addressing the policy alternatives and the politics necessary to create good legislation. We help to dispel myths, challenge conventional wisdom, and expand the dialogue.

Founded by Robert Kuttner, Paul Starr, and Robert Reich, read the original 1989 prospectus for the magazine.

To learn more about our history, check out this 2015 piece by Starr and Kuttner, reflecting on 25 years of politics and change.

American Prospect, Inc., is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporation headquartered in Washington, D.C.

You can support our mission with a subscription or a tax-deductible donation.

Spread the word